This post is not related to financial reporting issues, but it does relate to accounting education.

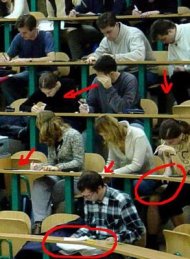

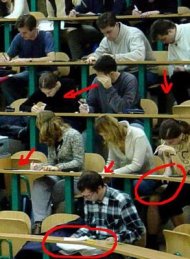

First, a little history. Accounting professors tend to mostly have tests that require the regurgitation of factual content. Questions are similar to: Do you know this? Do you know that? Can you compute this accounting number? And so forth. To do well on tests, students have to memorize. Naturally, students are concerned about their memories holding up. They fear forgetting, so they hedge their chances by cheating. It has been shown many times that cheating is rampant in both business courses and accounting courses. Professors think cheating is terrible, students don’t. Students reason that they already knew the material, so cheating on the test isn’t as bad as, say, axe murder. Students are so good at cheating on tests that professors rarely catch them. If you ever see a professor walking around a test room, chances are the professor is wearing a scowl. He/she is unhappy about not catching all the students that undoubtedly are cheating on the test.

First, a little history. Accounting professors tend to mostly have tests that require the regurgitation of factual content. Questions are similar to: Do you know this? Do you know that? Can you compute this accounting number? And so forth. To do well on tests, students have to memorize. Naturally, students are concerned about their memories holding up. They fear forgetting, so they hedge their chances by cheating. It has been shown many times that cheating is rampant in both business courses and accounting courses. Professors think cheating is terrible, students don’t. Students reason that they already knew the material, so cheating on the test isn’t as bad as, say, axe murder. Students are so good at cheating on tests that professors rarely catch them. If you ever see a professor walking around a test room, chances are the professor is wearing a scowl. He/she is unhappy about not catching all the students that undoubtedly are cheating on the test.

This type of cheating bleeds over to the writing of papers. Paper assignments in accounting courses tend to require students to look up information and regurgitate it onto a written paper. Glom it and vomit. These days the research is conducted on-line, locating articles appearing in digital media. It is easy to cut text directly out of an on-line article, and paste it directly into a student’s paper. Without attribution, if course. According to current academic rules, this is cheating. Those wonderfully written passages found on the web are supposed to be paraphrased into the paper, not pasted onto the paper. Professors on their high horse are ready to punish students for plagiarism with an F in the course and academic suspension. Students think this is going way too far.

This type of cheating bleeds over to the writing of papers. Paper assignments in accounting courses tend to require students to look up information and regurgitate it onto a written paper. Glom it and vomit. These days the research is conducted on-line, locating articles appearing in digital media. It is easy to cut text directly out of an on-line article, and paste it directly into a student’s paper. Without attribution, if course. According to current academic rules, this is cheating. Those wonderfully written passages found on the web are supposed to be paraphrased into the paper, not pasted onto the paper. Professors on their high horse are ready to punish students for plagiarism with an F in the course and academic suspension. Students think this is going way too far.

Unfortunately for students, in 2009 it is much easier for professors to catch students plagiarizing on papers than it is to catch them on tests. If a professor suspects a student of plagiarizing, then the professor can easily do a google search on the suspect wording and quickly catch a student in the act! When this happens, the student is screwed. And how! University rules and policies permit, even encourage, professors to assign the grade of F. A student also can get suspended or expelled. A nuke!

Unfortunately for students, in 2009 it is much easier for professors to catch students plagiarizing on papers than it is to catch them on tests. If a professor suspects a student of plagiarizing, then the professor can easily do a google search on the suspect wording and quickly catch a student in the act! When this happens, the student is screwed. And how! University rules and policies permit, even encourage, professors to assign the grade of F. A student also can get suspended or expelled. A nuke!

Just about any professor (it doesn’t have to be an accounting professor) hates cheating or plagiarizing. When two or more professors gather together, they frequently rail against it. Cheating and plagiarizing garner more complaints than either death or taxes.

Yet, professors remain human with a modicum of compassion. When it comes right down to it they are reluctant to nuke a cheating student. So, what to do? They think that something should be done, but they don’t want to ruin a student’s academic career.

M. Garrett Bauman, a retired English professor, has written the latest Chronicle of Higher Education story on plagiarism. After a few paragraphs retelling popular faculty attitudes towards plagiarized work, he suggests that we should play or toy with students that plagiarize, just like he did once. His story is amusing, I guess, in the same way we are amused when a cat plays with a captured mouse. Of course, it is not amusing to the mouse. The mouse must feel its rights have been violated. If it can get past the terror.

story is amusing, I guess, in the same way we are amused when a cat plays with a captured mouse. Of course, it is not amusing to the mouse. The mouse must feel its rights have been violated. If it can get past the terror.

After students plagiarize anyway, release your inner crime-scene investigator and make catching them a sport instead of a chore. For example, you can amuse yourself by directing your own morality play to lead a felon to his fate. Here’s how I did it once:

David’s shoulder-length hair, trimmed beard and mustache, soft eyes, and mild manner were reminiscent of Jesus. His writing was clichéd and immature. Then he handed in a scintillating paper containing words like “winsome,” “beguiling,” and “Krishna.” I called him to my office. “This is quite a paper, David.”

“Thank you.” He blinked his Jesus eyes and stroked his long, soft hair.

“I do have a few tiny questions. Here on Page 2, you used the word ‘charlatan.’ What does that mean?”

“Don’t you know?”

“Enlighten me.”

“Uh, well, it’s like an idol that people worship. I think he was a king.”

“Kind of like Charlemagne?”

“Right.”

“I see. How about ‘salutary’ here on Page 3?”

He shrugged. “That’s being alone.”

“I think that’s ‘solitary.’ This is ‘salutary.’ See?”

“I guess I typed it wrong. I meant ‘solitary.'”

“‘Solitary’ makes no sense. ‘Salutary’ fits perfectly.”

“It does?”

“Yes. Actually, it’s quite professional.” I tapped the paper, leaned closer, and whispered confidentially: “How is it that you use such words and don’t know their meaning?” Delightful little beads formed on David’s forehead.

He blinked several times. “Uh, I guess the right word just comes to me.”

“Like, you’re inspired?”

“Exactly!” He hugged the word “inspired.”

“Amazing. You must have been catatonic when you wrote it.”

“Well” He smiled, hoping I had complimented him.

“I’m sure the dean would love to chat with you about this um ability.”

“Aw, no, he wouldn’t.” David glanced at the door.

“Oh, he would. You wrote this with no help whatsoever.” I shook my head. “Amazing.”

David snapped his fingers. “You know what? I just remembered that I used the computer thesaurus a few times. You know, to build up my vocabulary.”

“Ah! But isn’t it odd you forgot the definitions?”

“I wrote the paper a while ago.” He shrugged off his weak memory.

“Strange, I read something on this topic recently.” I pulled the download from my drawer. “The author uses many vocabulary words you do. Whole passages, in fact. Look here. See? And here.” His head bent pretending to read, but his eyes were squeezed shut, awaiting the ax. I couldn’t resist one last little twist. “David, do you think some unscrupulous author saw your paper somewhere and copied it?”

His head shot up. “Really?”

I smiled beatifically.

I doubt that I could ever deal with a student the way Bauman tells of it. It’s too cruel for my taste. But, perhaps he has a point. There could be proportionate liability for those caught plagiarizing. I mean, audit firms have for decades grappled with the issue of what audit opinion to render after finding shortcomings in a client company’s work. Too often the company is let off with a warning, “Don’t do it again.” But of course, they frequently do. Perhaps our plagiarizing students are best dealt with by scaring them (if it can be done), then letting them go. A catch and release policy, if you will. Perhaps it is a punishment more fitting to the crime. Maybe not.

I shared this CHE article over on AECM, the e-mail list for accounting professors. Bob Jensen responded, reminiscing about “… how hard it was in the good old days to detect plagiarism. One of my high school history teachers said that after 30 years of teaching she warned in advance that she knew encyclopedia passages by heart, including passages on Napoleon, Thomas Jefferson, and other popular topics for history papers. She also had two of the most popular encyclopedia sets in her home where she graded papers.”

Bob’s memories are the best stories.

Debit and credit – – David Albrecht

Read Full Post »

There are several controversies in financial reporting. These are all either or, with no compromise available. Here are a few just off the top of my head:

There are several controversies in financial reporting. These are all either or, with no compromise available. Here are a few just off the top of my head: